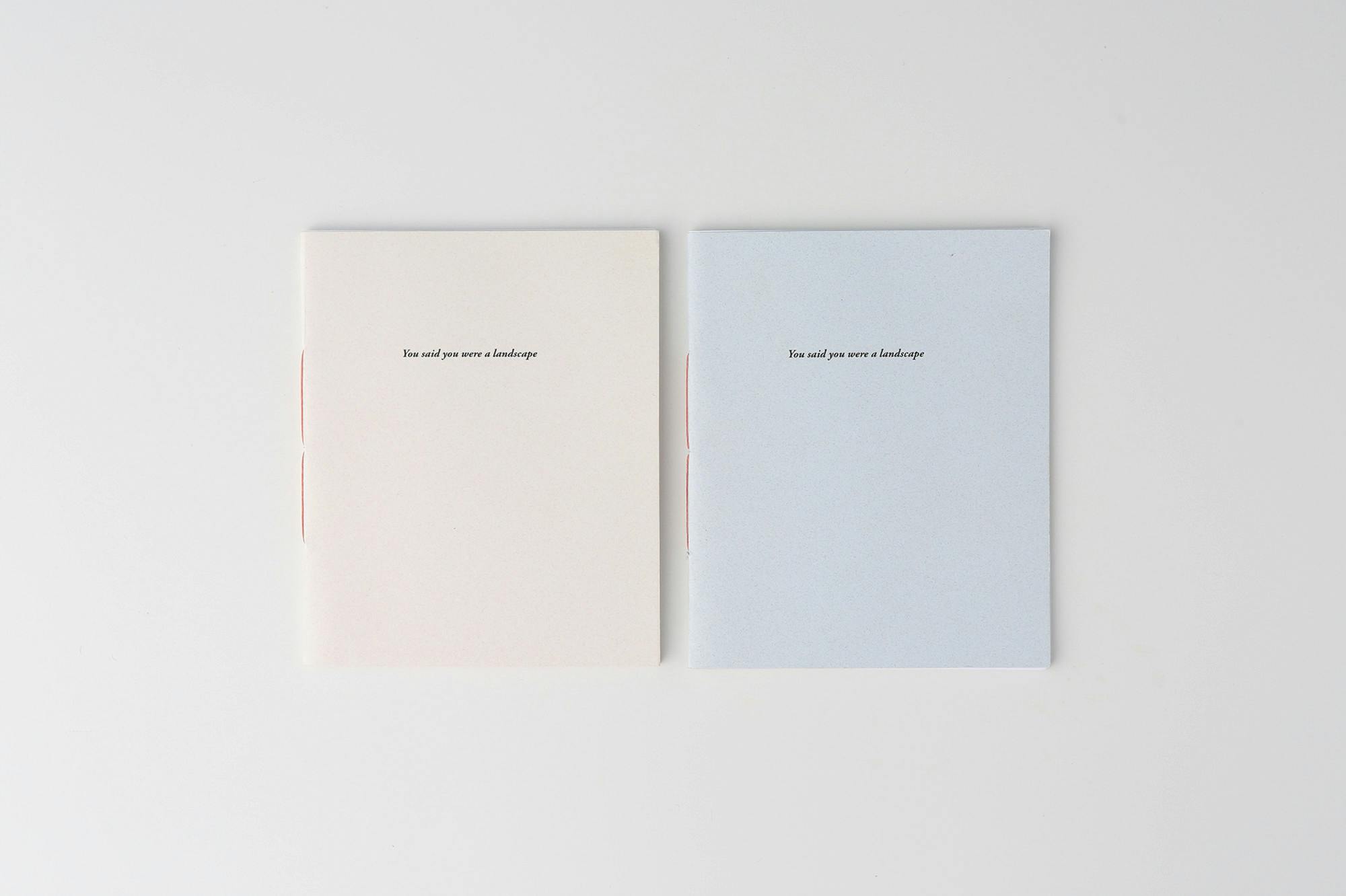

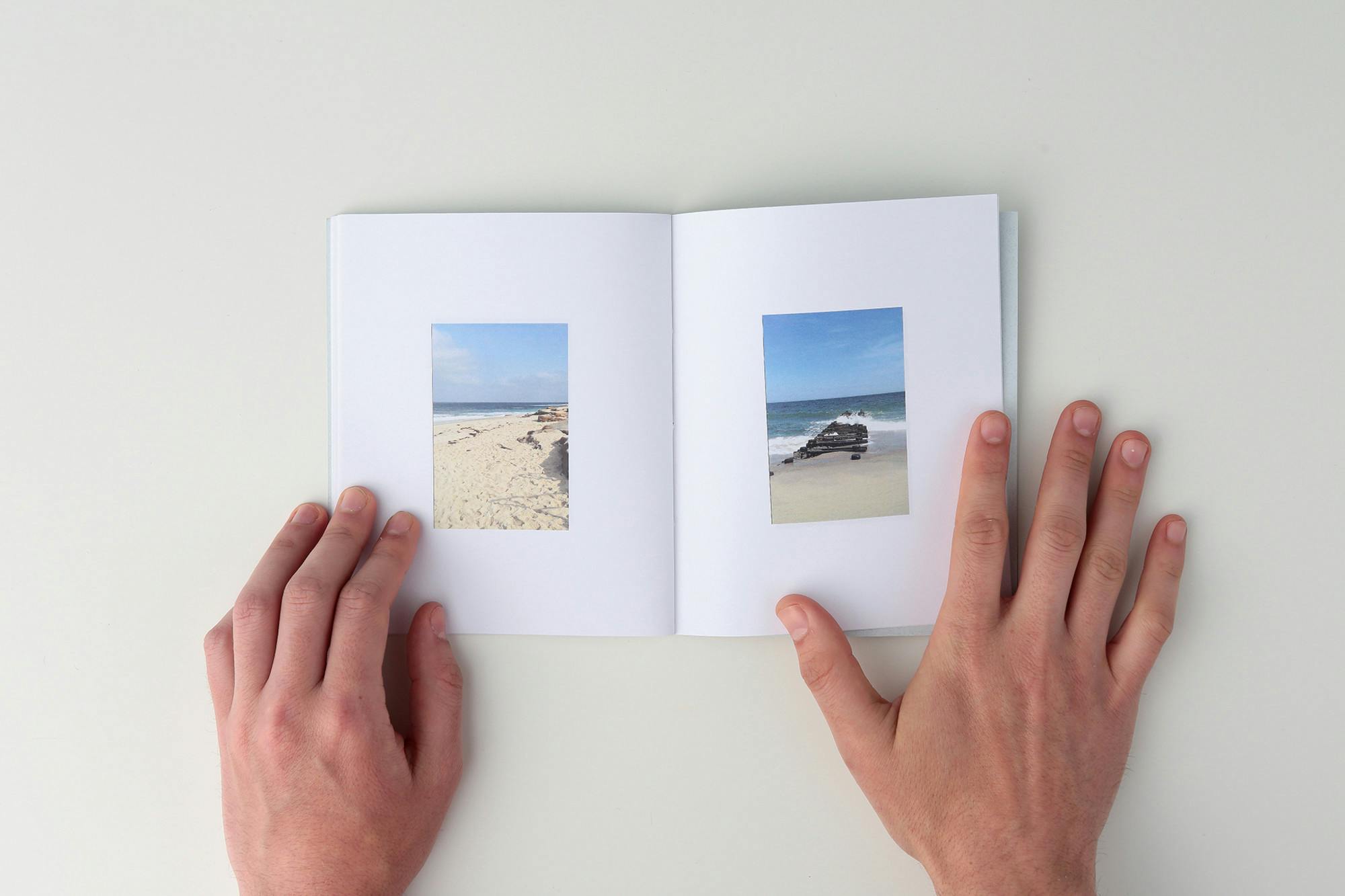

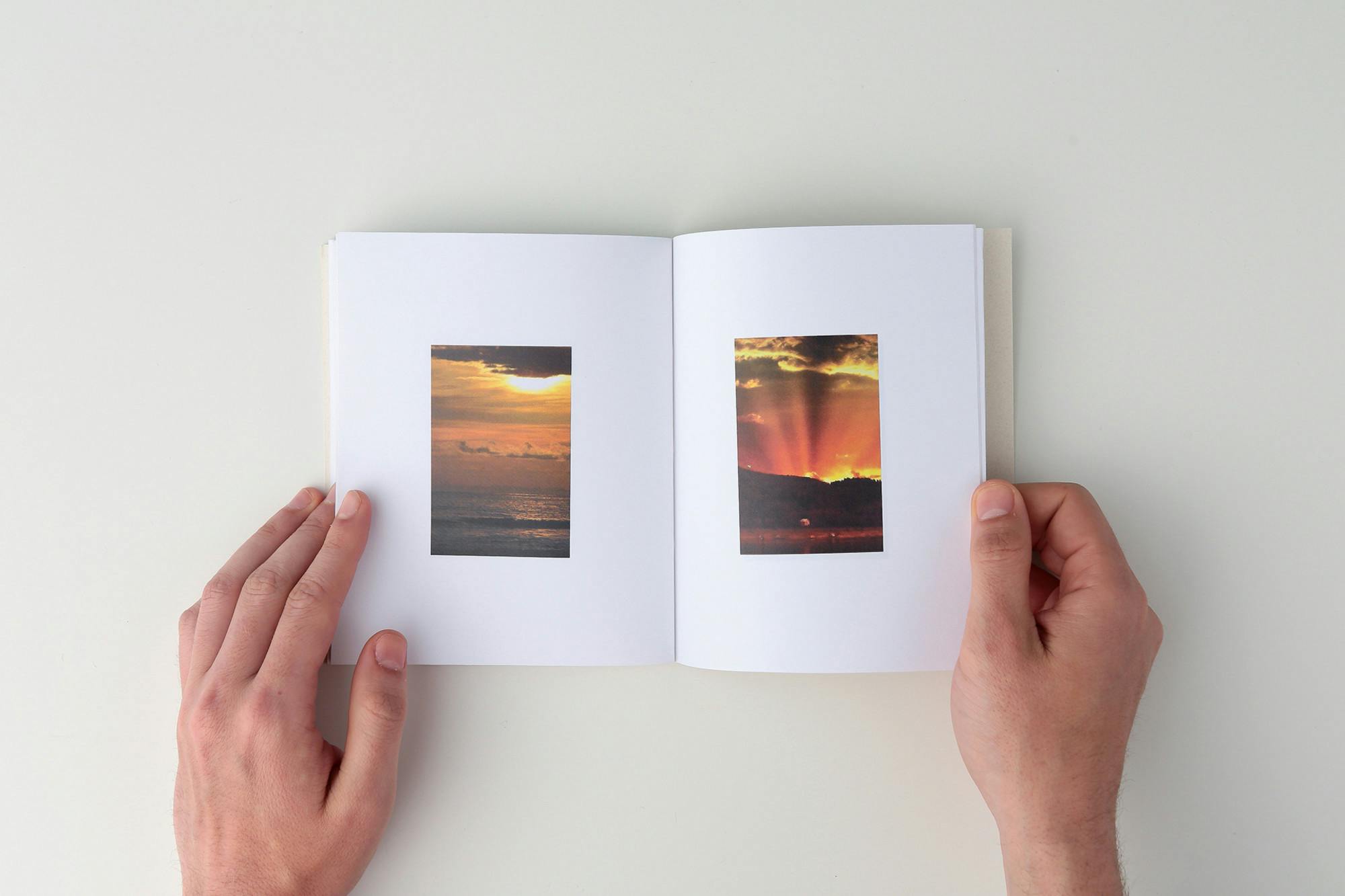

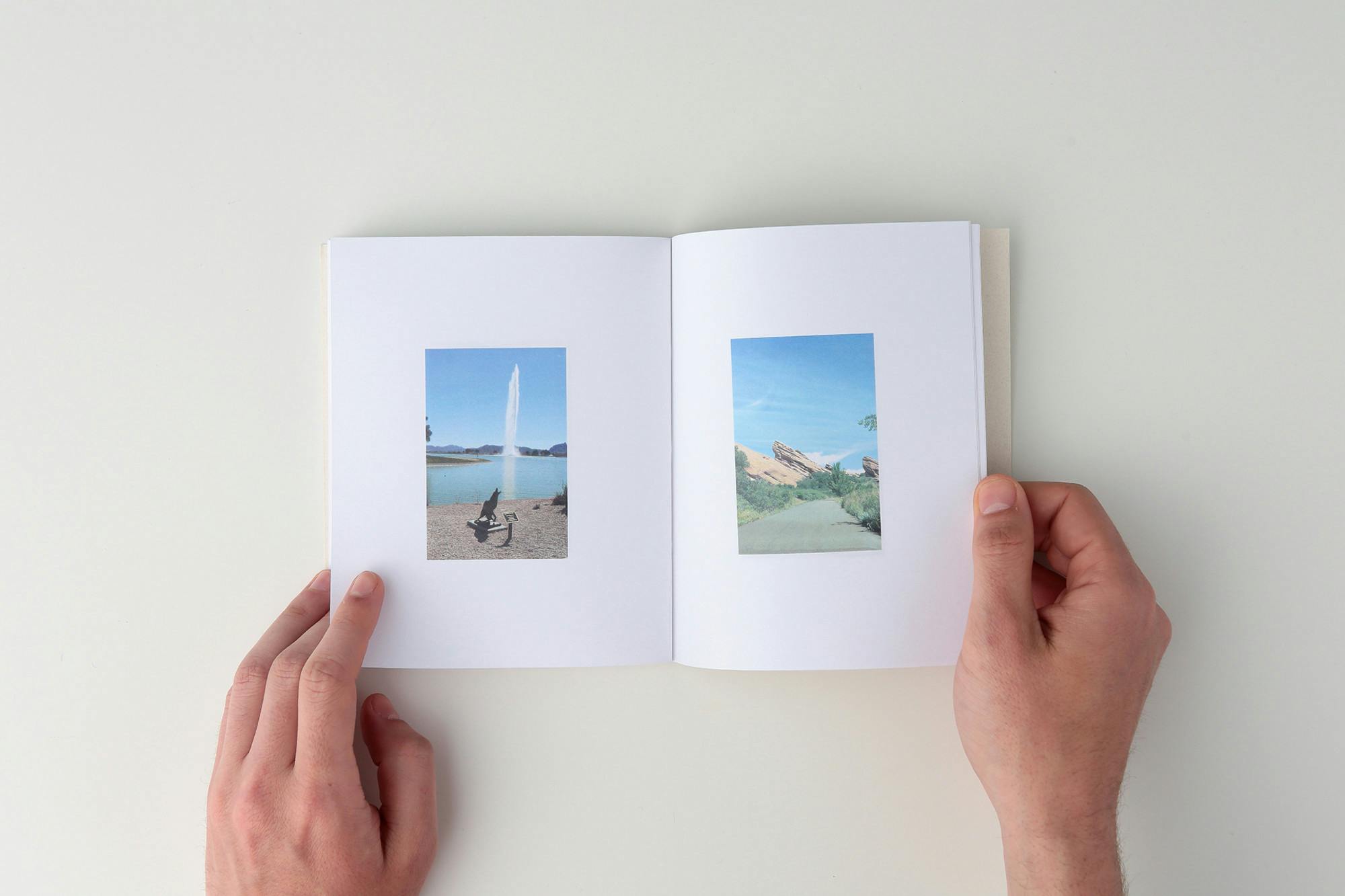

You said you were a landscape, 2013

hand-stitched, color, 48 pages; two volumes, numbered of 10

Essay by Ben Joffe

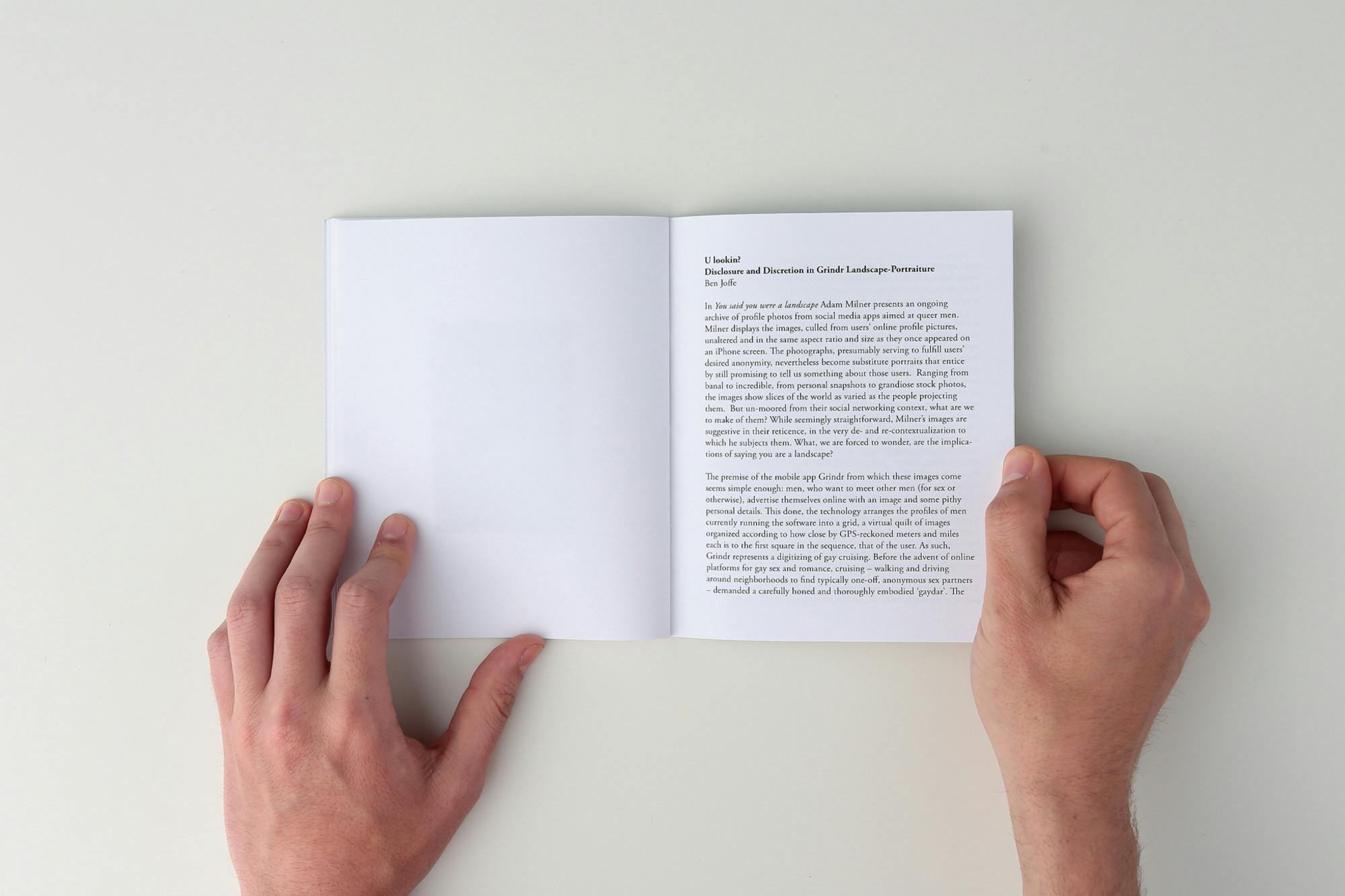

U lookin?

Disclosure and Discretion in Grindr Landscape-Portraiture

Ben Joffe

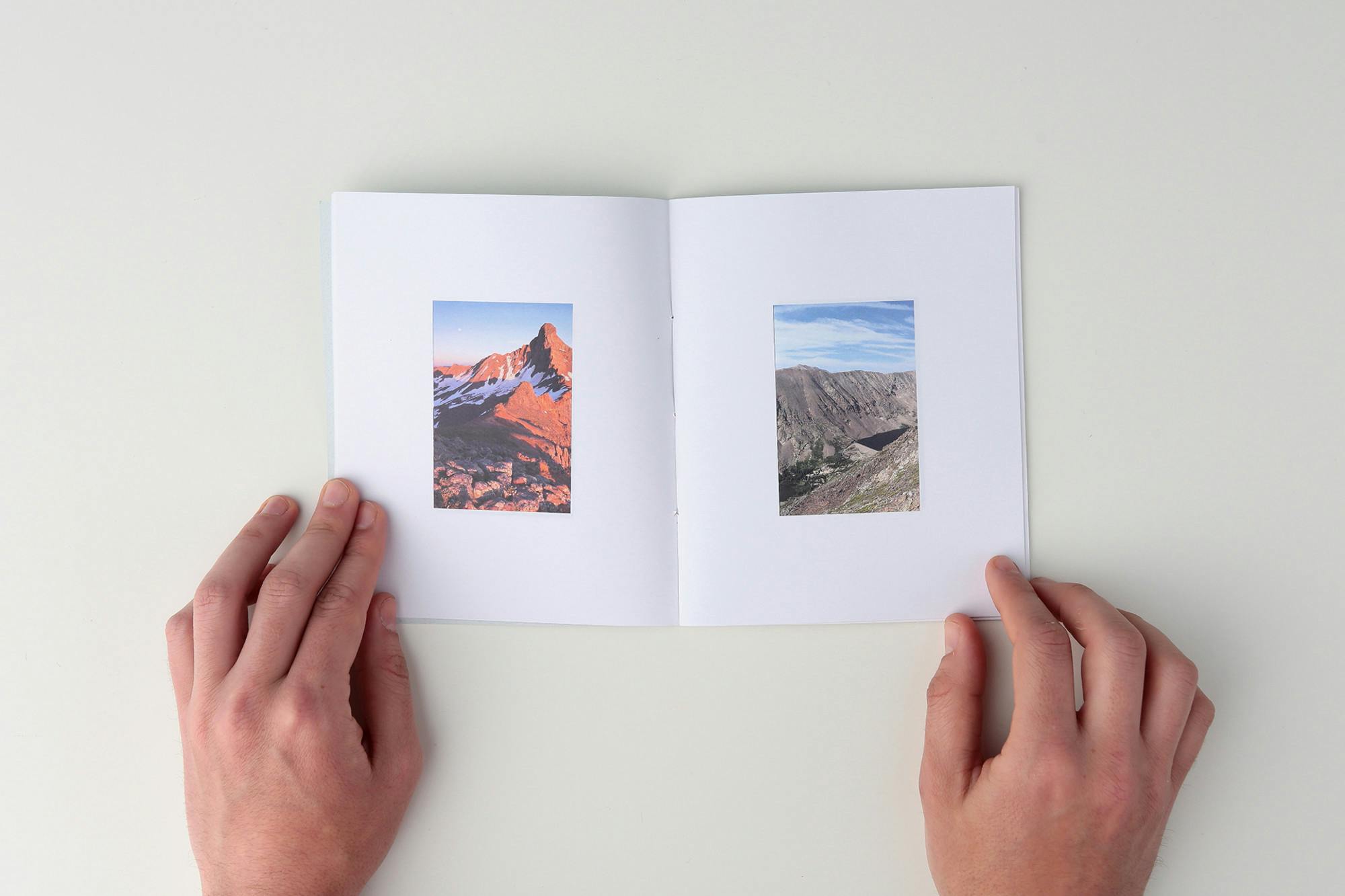

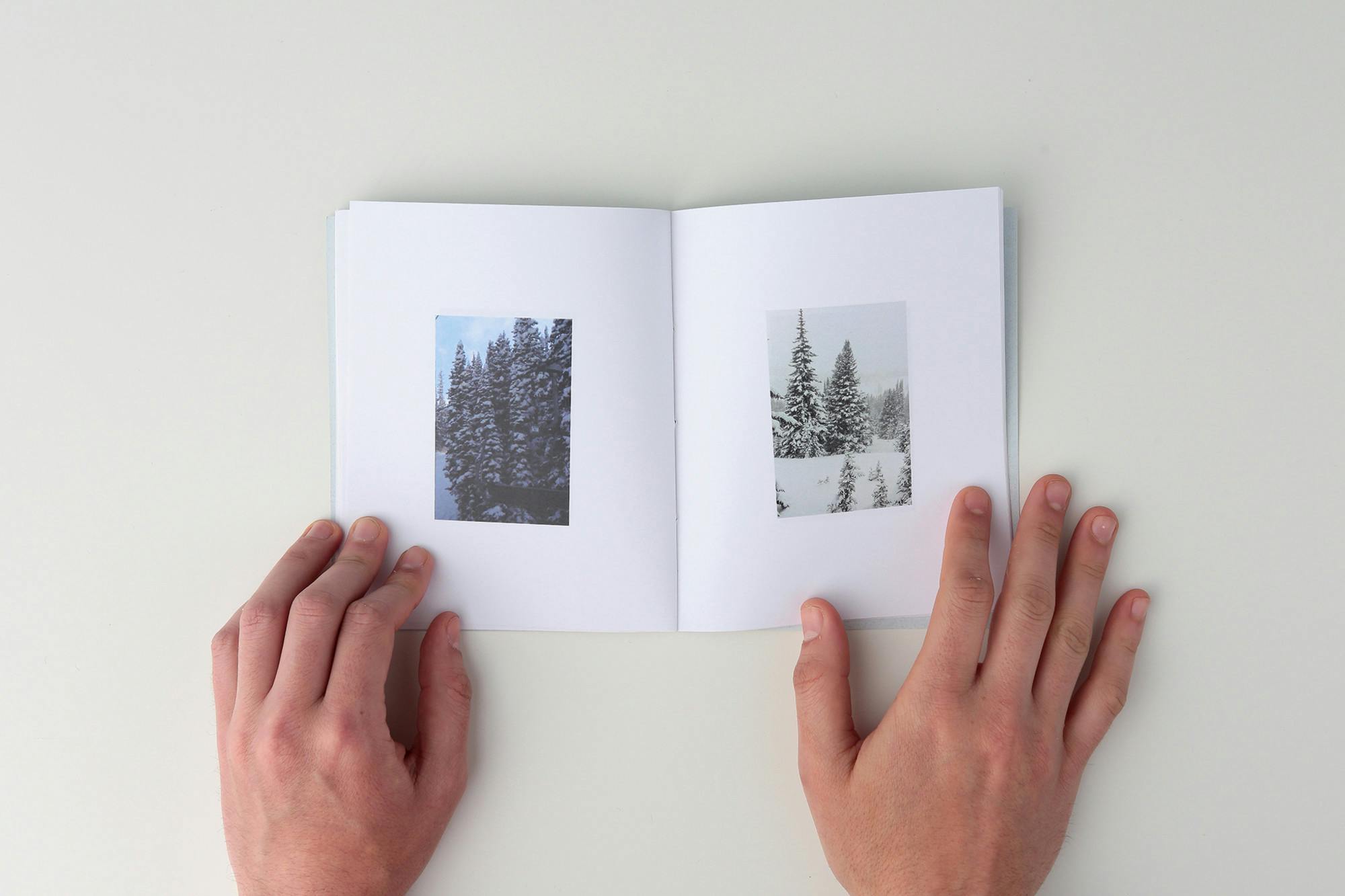

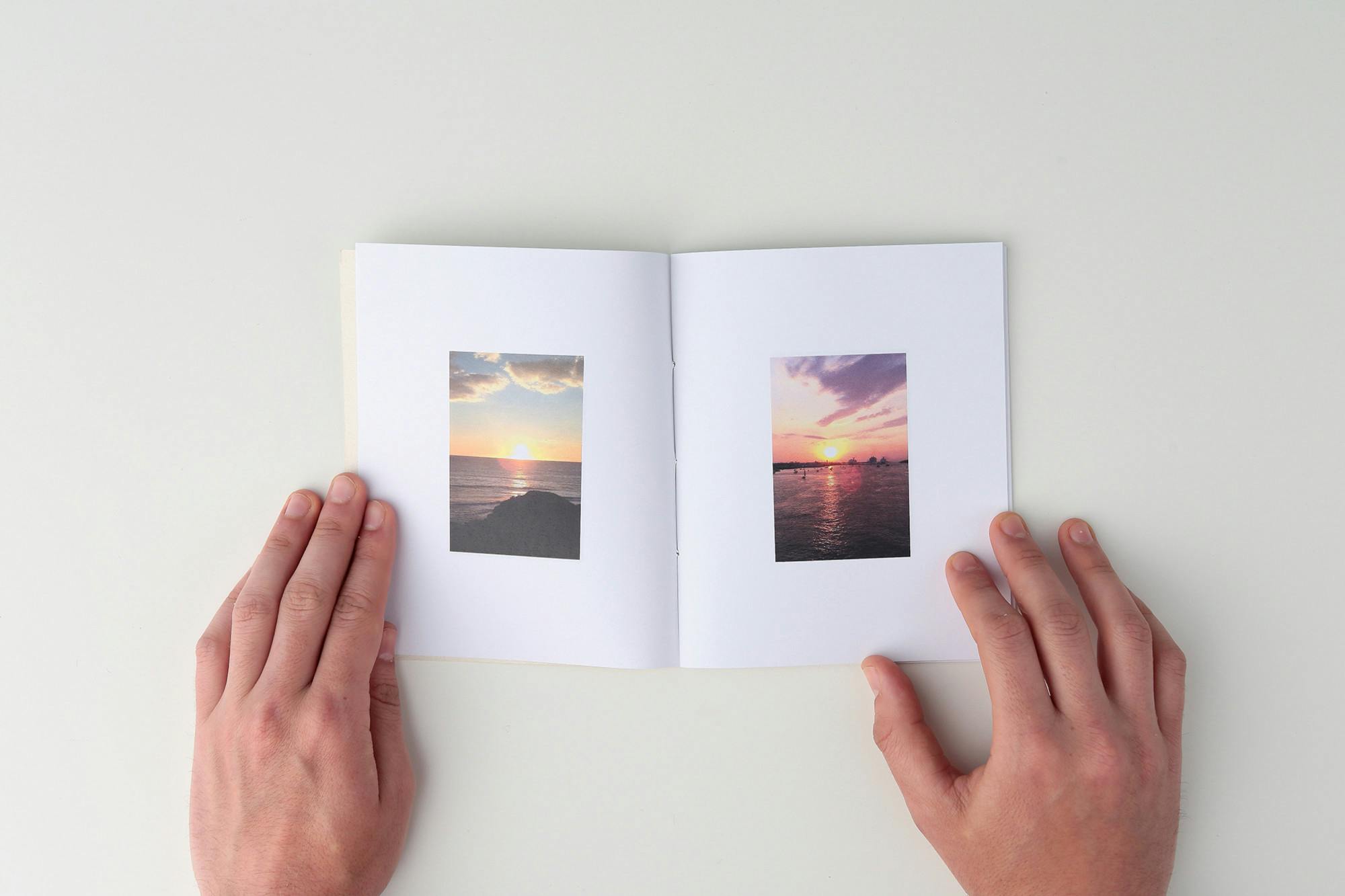

In You said you were a landscape Adam Milner presents an ongoing archive of profile photos from social media apps aimed at queer men. Milner displays the images, culled from users’ online profile pictures, unaltered and in the same aspect ratio and size as they once appeared on an iPhone screen. The photographs, presumably serving to fulfill users’ desired anonymity, nevertheless become substitute portraits that entice by still promising to tell us something about those users. Ranging from banal to incredible, from personal snapshots to grandiose stock photos, the images show slices of the world as varied as the people projecting them. But unmoored from their social networking context, what are we to make of them? While seemingly straightforward, Milner’s images are suggestive in their reticence, in the very de- and re-contextualization to which he subjects them. What, we are forced to wonder, are the implications of saying you are a landscape?

The premise of the mobile app Grindr from which these images come seems simple enough: men, who want to meet other men (for sex or otherwise), advertise themselves online with an image and some pithy personal details. This done, the technology arranges the profiles of men currently running the software into a grid, a virtual quilt of images organized according to how close by GPS-reckoned meters and miles each is to the first square in the sequence, that of the user. As such, Grindr represents a digitizing of gay cruising. Before the advent of online platforms for gay sex and romance, cruising – walking and driving around neighborhoods to find typically one-off, anonymous sex partners – demanded a carefully honed and thoroughly embodied ‘gaydar’. The extra-sensory perception of expert cruising called for mastery of extensive vocabularies of fleeting eye and body contact, and meant coming to know and to internalize alternative topographies of and for safety and sociality. Grindr promises, in theory, to simplify all this.

It used to be that cruising meant navigating actual landscapes, with bodies trained to safely negotiate them. Grindr has replaced older topographies of desire and intimacy with new, digital ones that demand new literacies. On Grindr, not all users reveal their faces; indeed a majority of profiles offer headless, shirtless torsos or close ups of other isolated body parts, like nipples, necks, feet, and biceps. Other users, as Milner shows us, opt for picturesque landscapes. Blank profiles, without any ‘shopfront’ image at all are also common. In real life cruising, men ‘looking’ can do just that – using their eyes and other sensory means they can appraise potential sex partners, read the subtle signs of body, behavior, and mutual attraction. On Grindr, users promise that they are ‘straight-acting’ and ‘masculine’, send carefully staged or strategically edited photographs, or insist on being ‘discreet’, and we are expected to take their word for it. Moreover, unlike offline cruisers, users state unambiguously what they are and aren’t looking for. “Only into tall, white guys. Not racist just a preference”, “Chill masc bro looking for similar”. This undisguised partiality – and the distinctly racist, sexist, and homophobic climate it arguably creates – has been frequently noted in opinion pieces and research on the app. Indeed, the mantra ‘No fats, no fems, no Asians’ has become emblematic of the lionization of an ideal of specifically white, athletic and straight-acting homosexuality, and a love of sameness that seems to flourish in queer men’s social networking environments.

With his archive of transposed portraits cum landscapes, Milner gestures adeptly at the displacement of one type of landscape by another, with all its uncertain implications. By his own account, Milner’s re-purposed images stand as “poetic, unsettling, beautiful, and confused reflections on our relationship to the places around us, each other, and ourselves.” They point to the ways in which Grindr opens up strange vistas of intimacy, distance, and uncertain boundaries, themes that permeate Milner’s work in general. The app’s constantly updating grid of available, desiring, and desirable men suggests a landscape of accessibility, creates the illusion of a dense demographic of viable sex partners, of inexhaustible options. And yet, despite the expanded possibilities of digital anonymity, online modes of communication preclude the benefits of sizing-up strangers in real life, while users’ unequivocal provisos cut short promises of utopian plenty. The idyllic scenes Milner presents to us, shorn of user statistics and details, float free and are transformed into open-ended, open-air questions, yet they are questions in which the possibility of foreclosure persists as a ghostly hypothetical.

Discretion and disclosure thus co-exist uneasily on Grindr. Grindr profiles, and faceless ones in particular, sit at a tense intersection of personal revelation and desire for anonymity and possibility. Jarring juxtapositions begin to seem inevitable. A photograph of a paradisiacal beach sports the caption ‘No blacks’, a stand of snow-covered trees atop a mountain seeks ‘bb’ (bareback, i.e. unprotected sex), a city skyline is interested in ‘ParTy-ing’ (wants to fuck on Tina, or methamphetamine). Milner’s curious snapshots permit us to wonder what disclaimers might have captioned each image, to ask what unsettling juxtapositions remain imaginable. Yet, in the end, by coupling his landscape-portraits stripped of all contextualizing information with an overarching title that gently alludes to their provenance, Milner artfully calls attention to his screenshots’ specific histories even as he denies, resists, and seeks to transcend them.