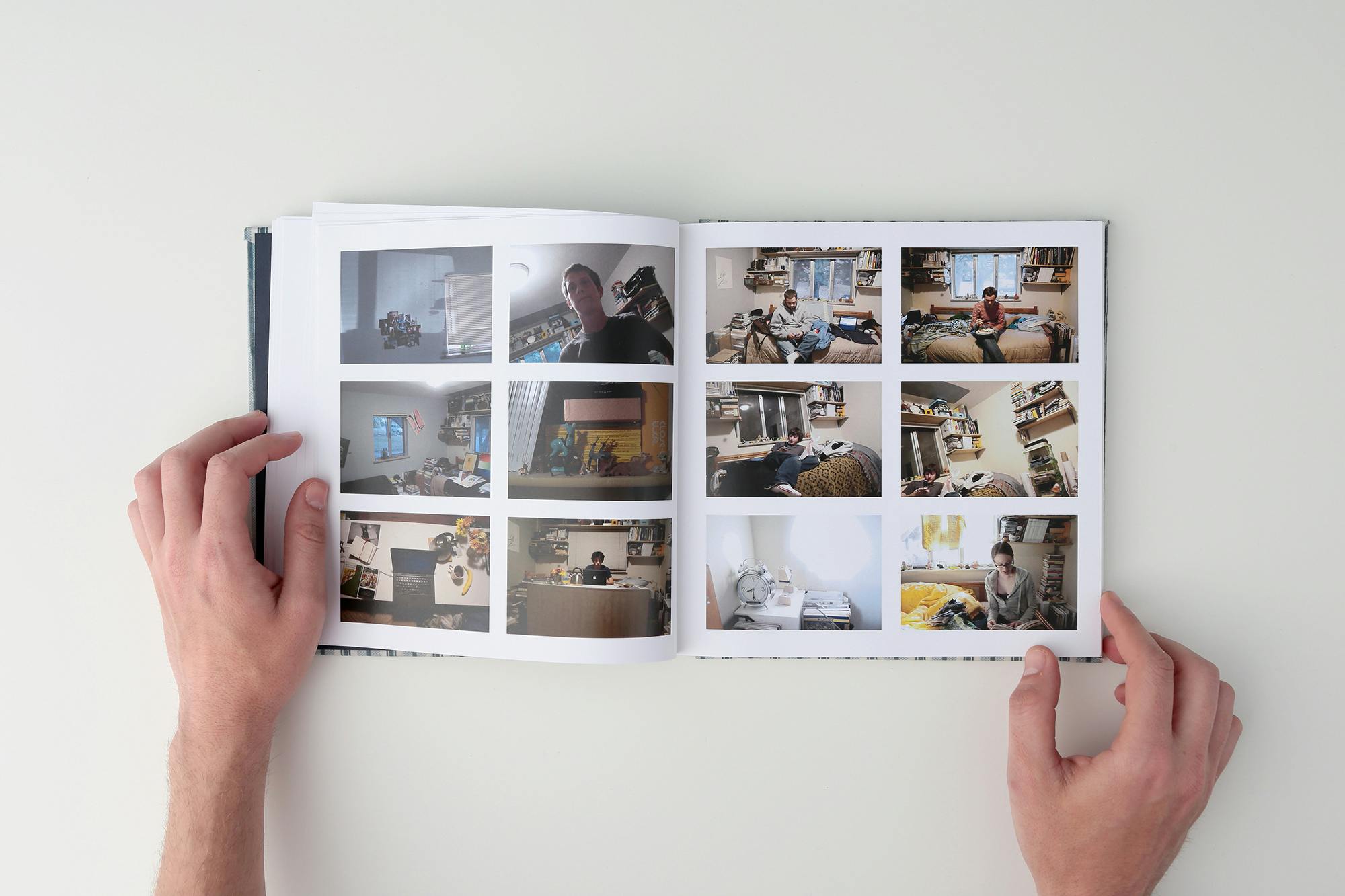

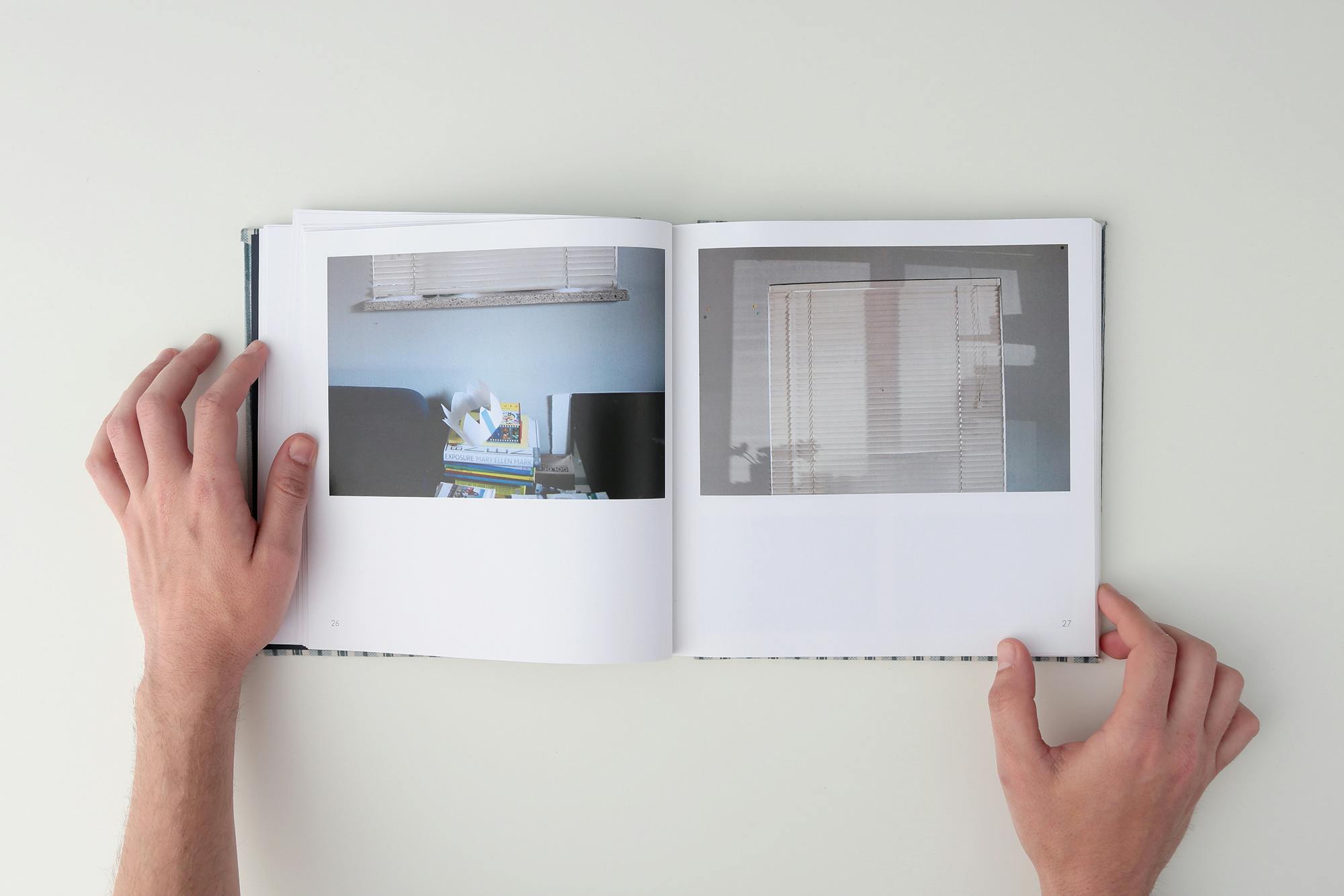

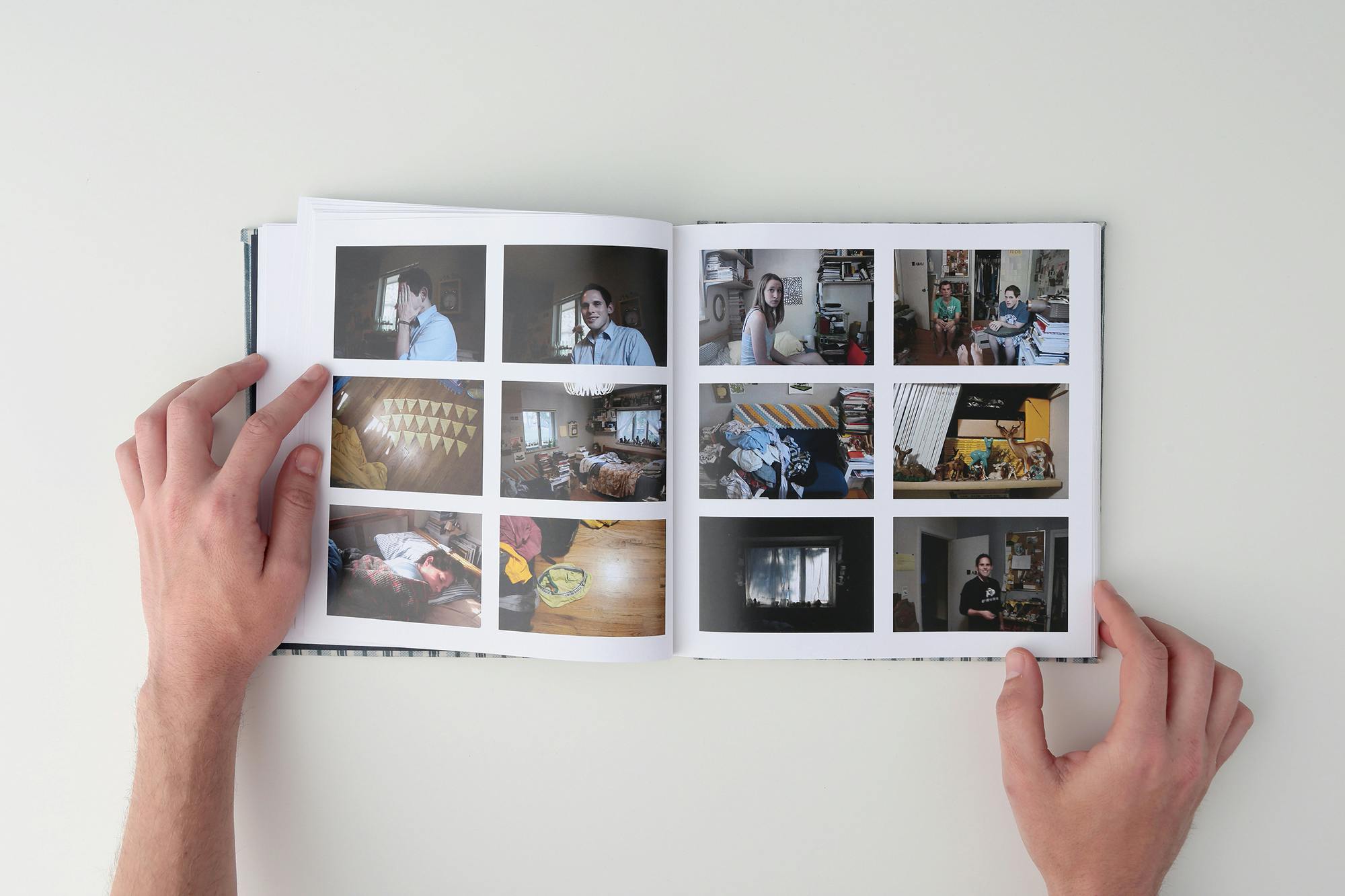

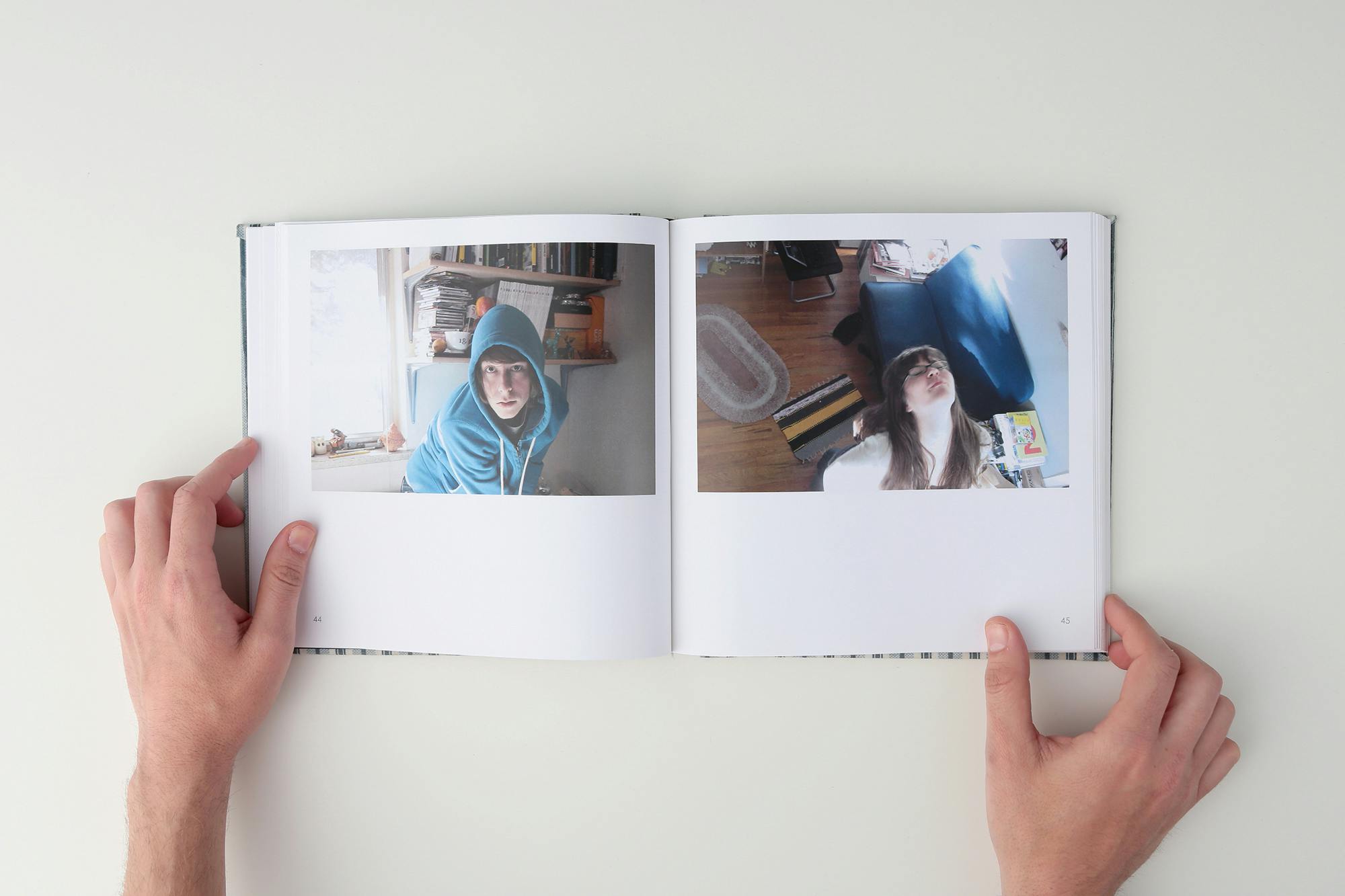

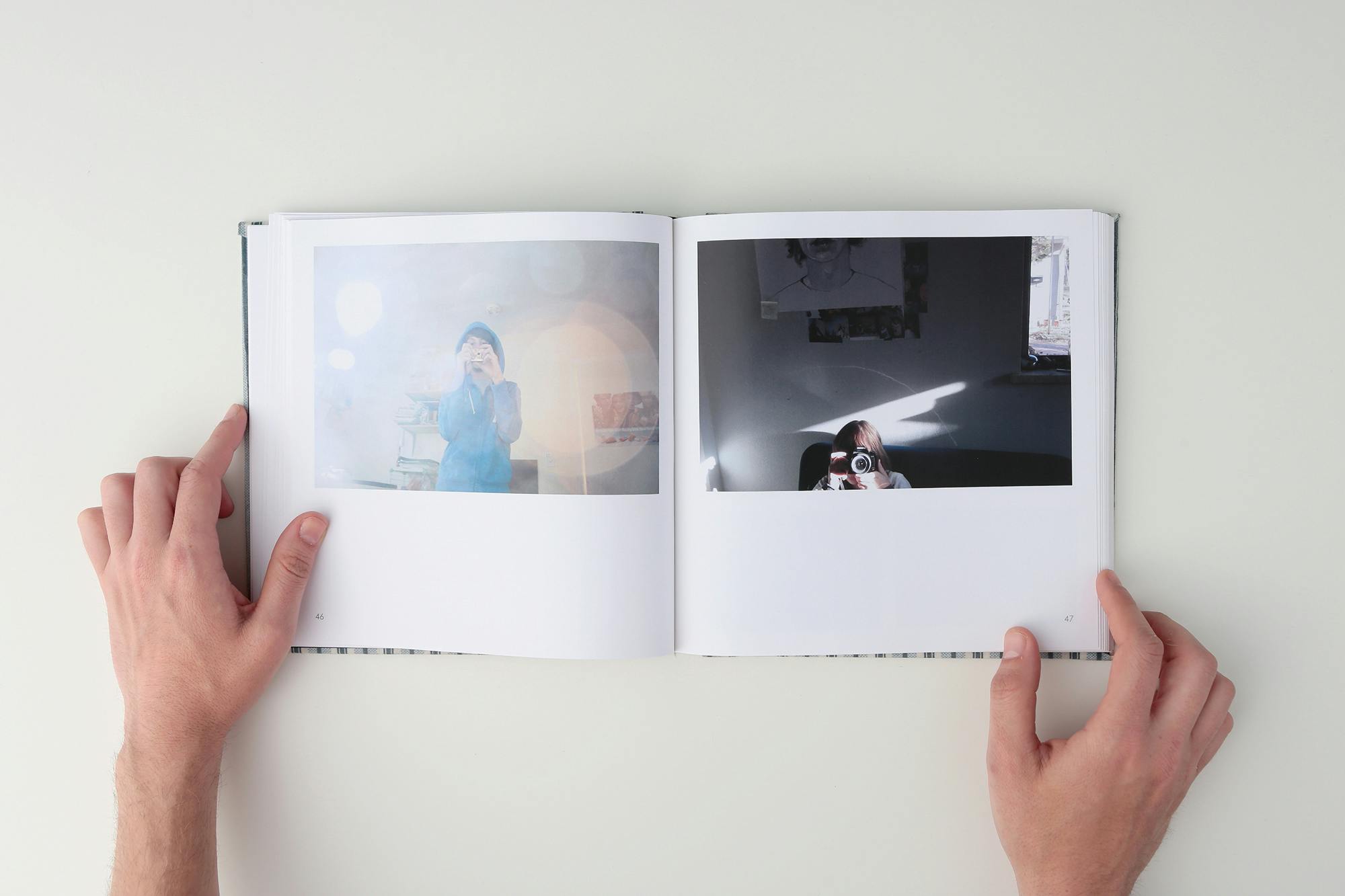

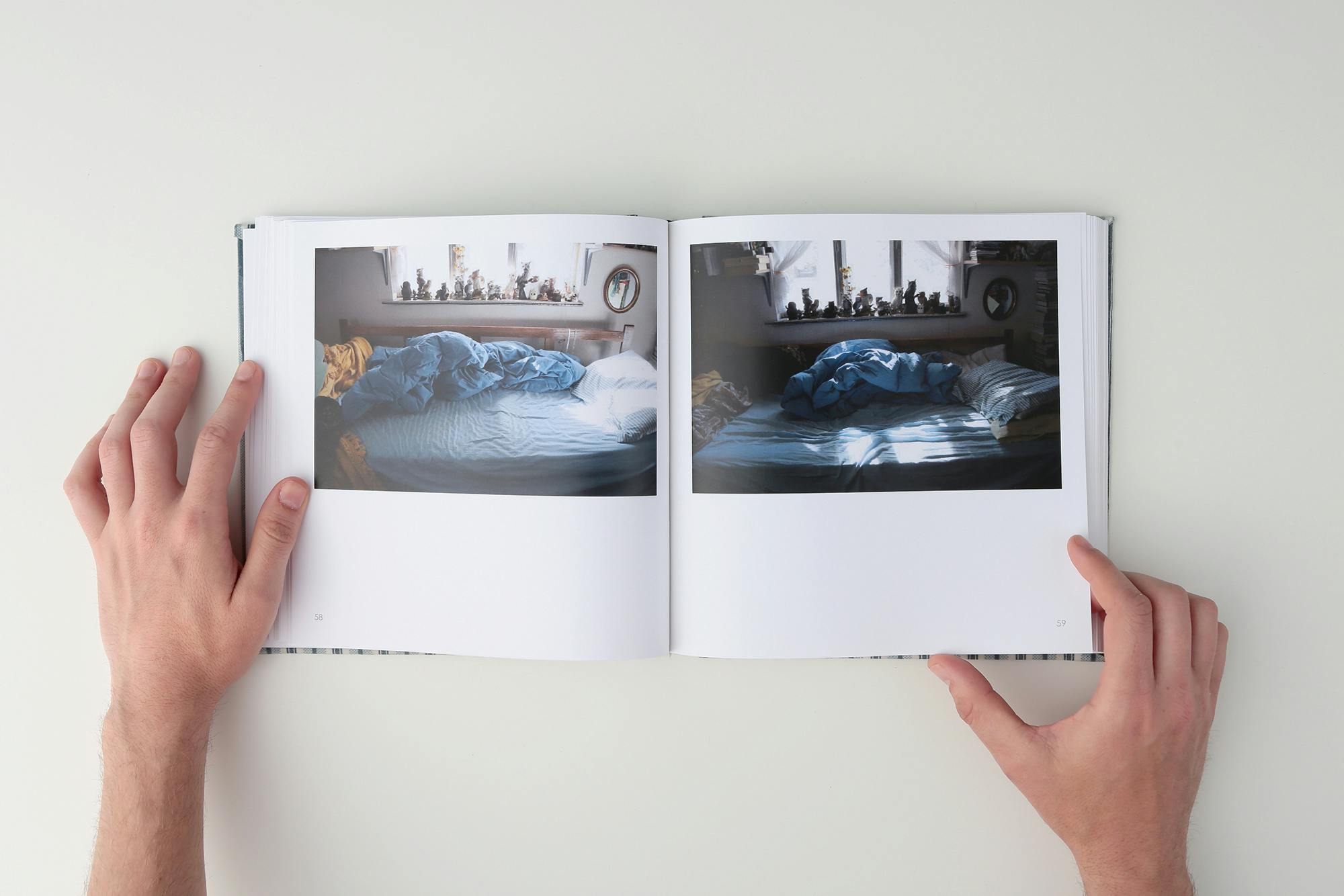

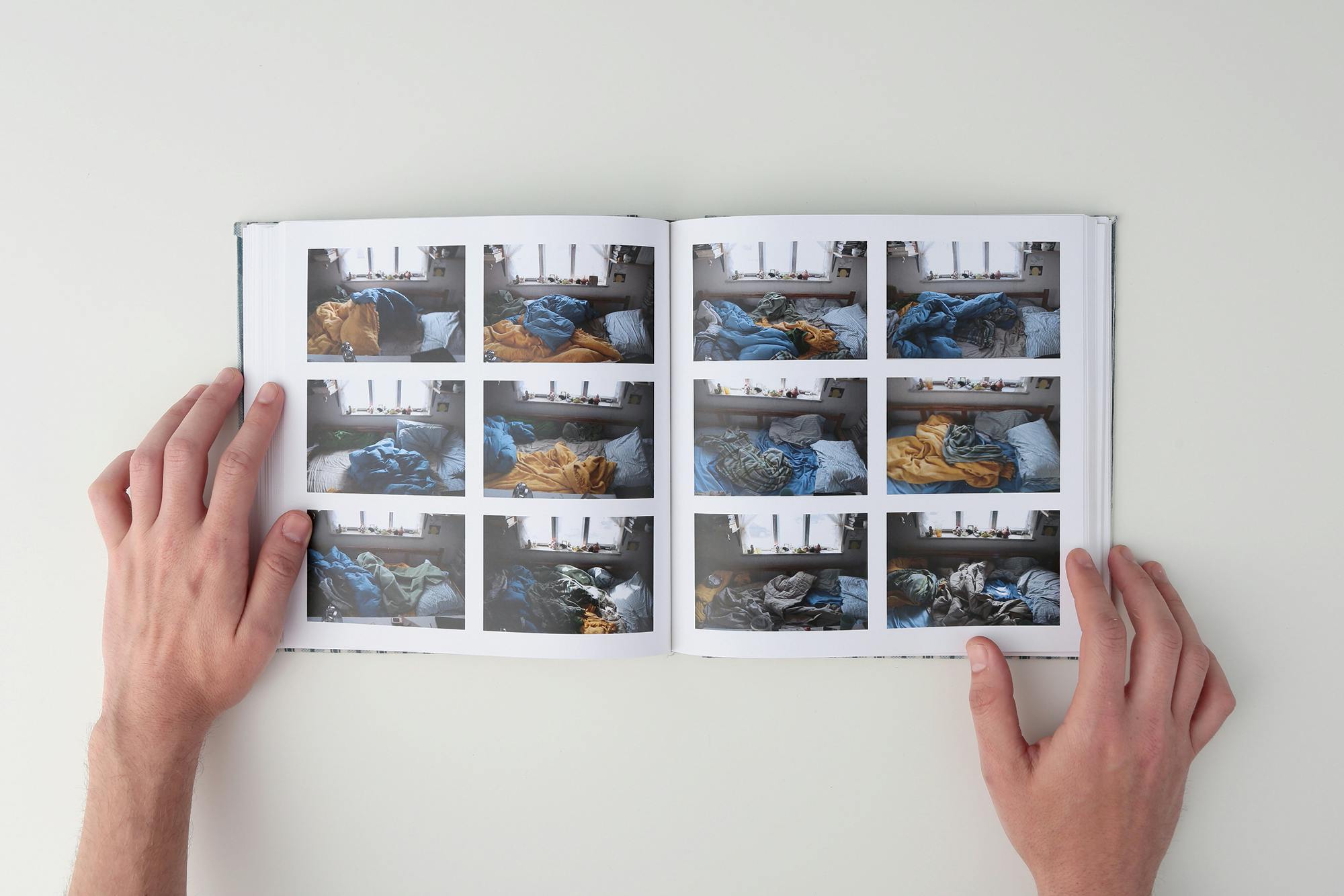

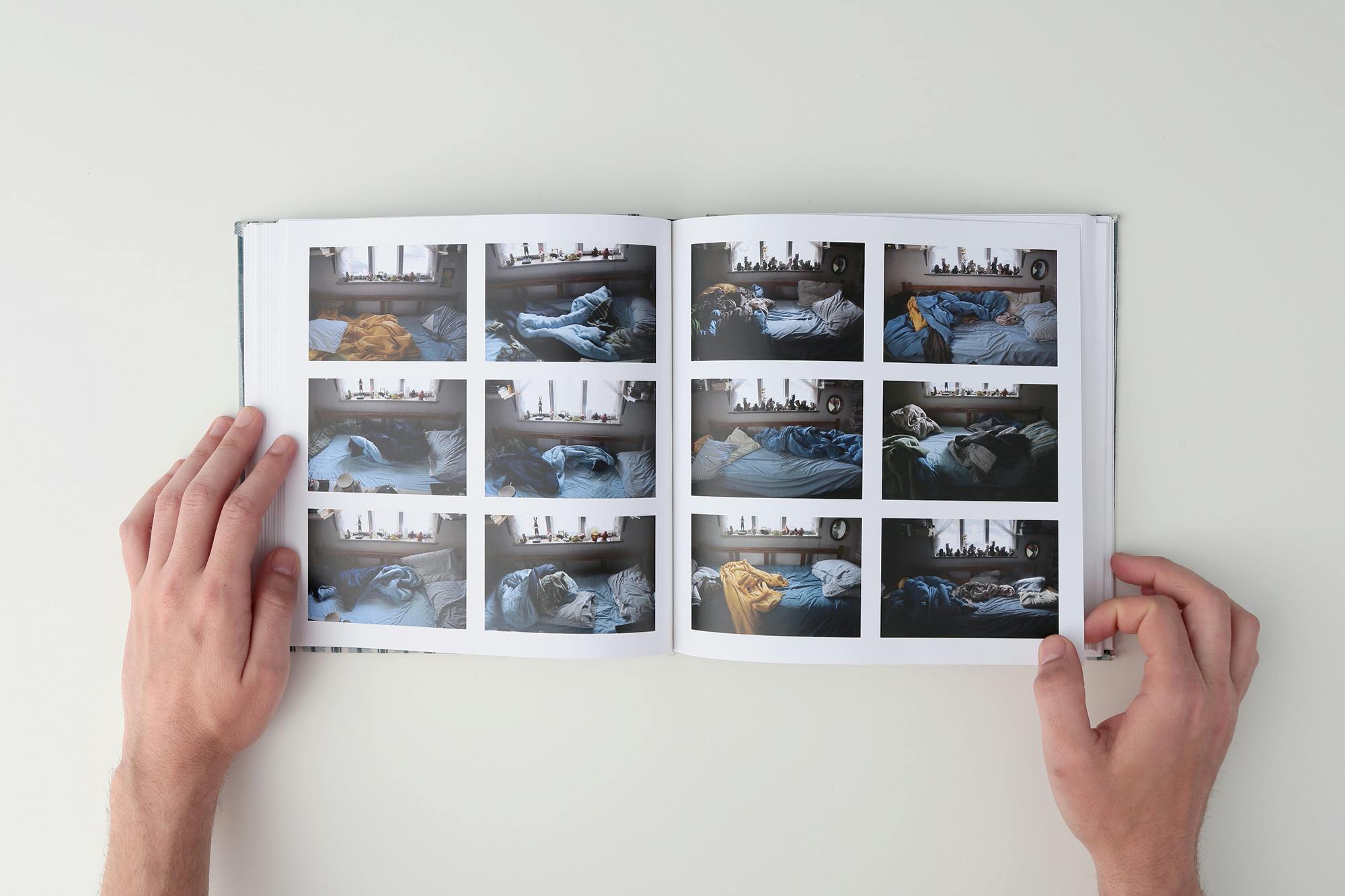

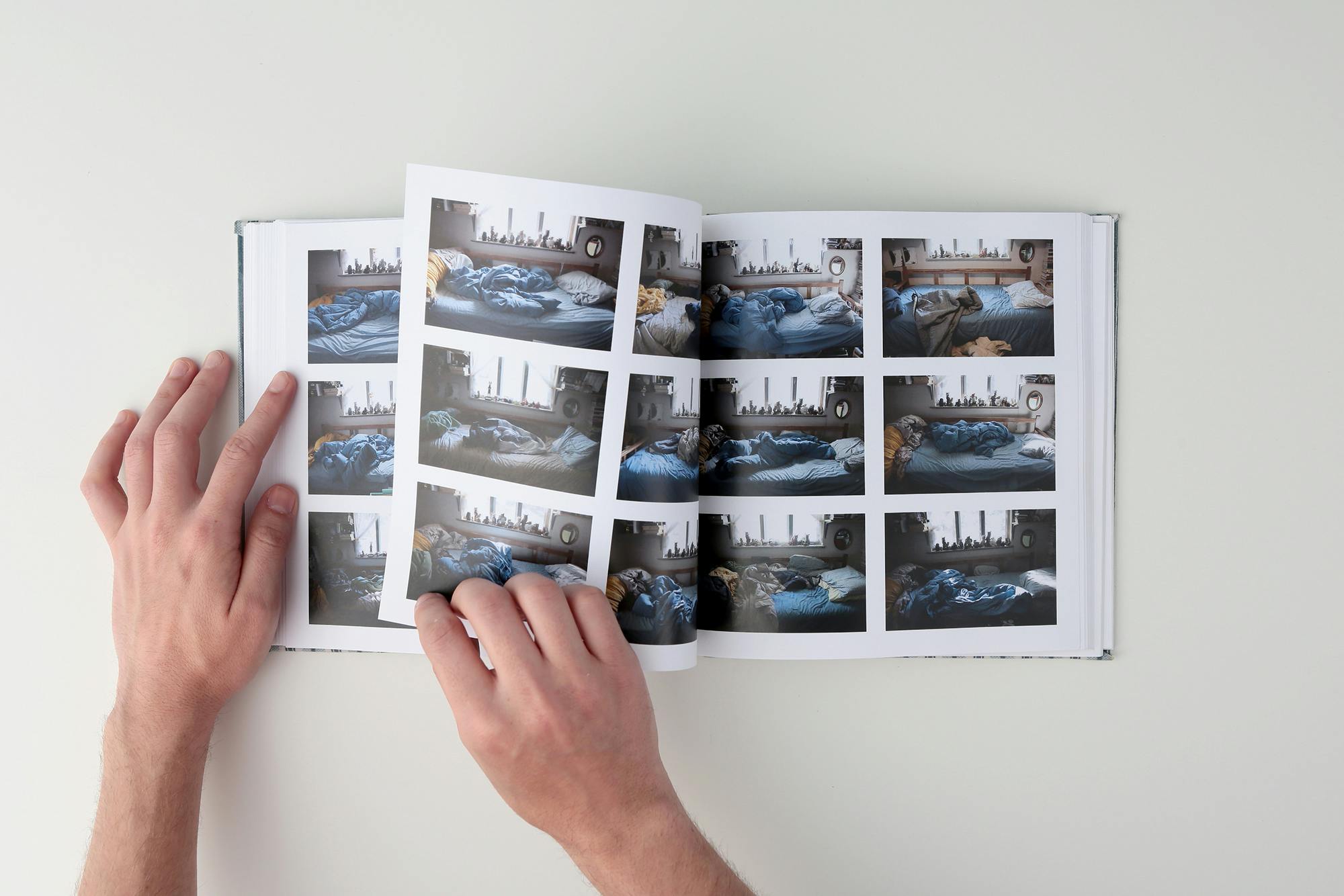

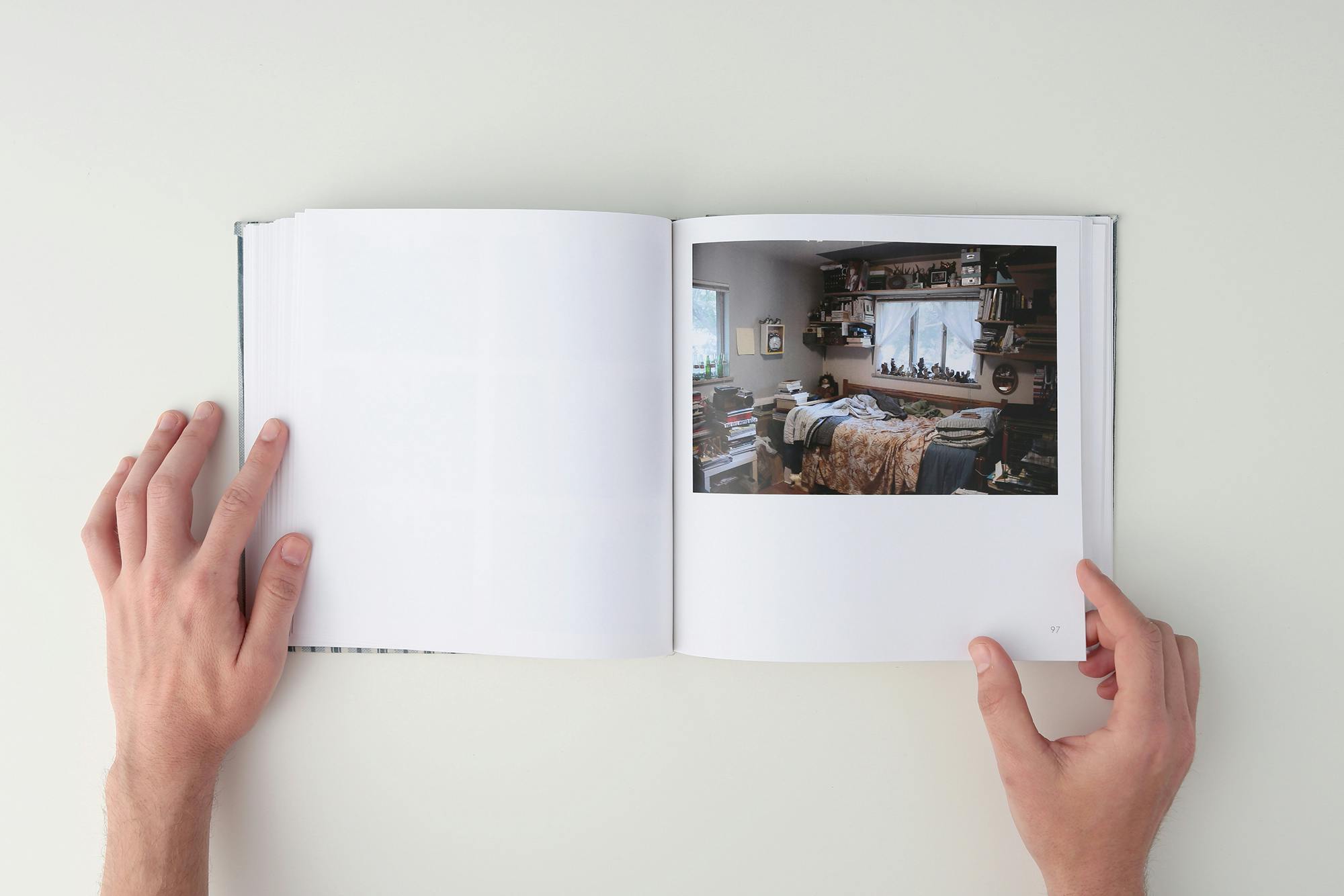

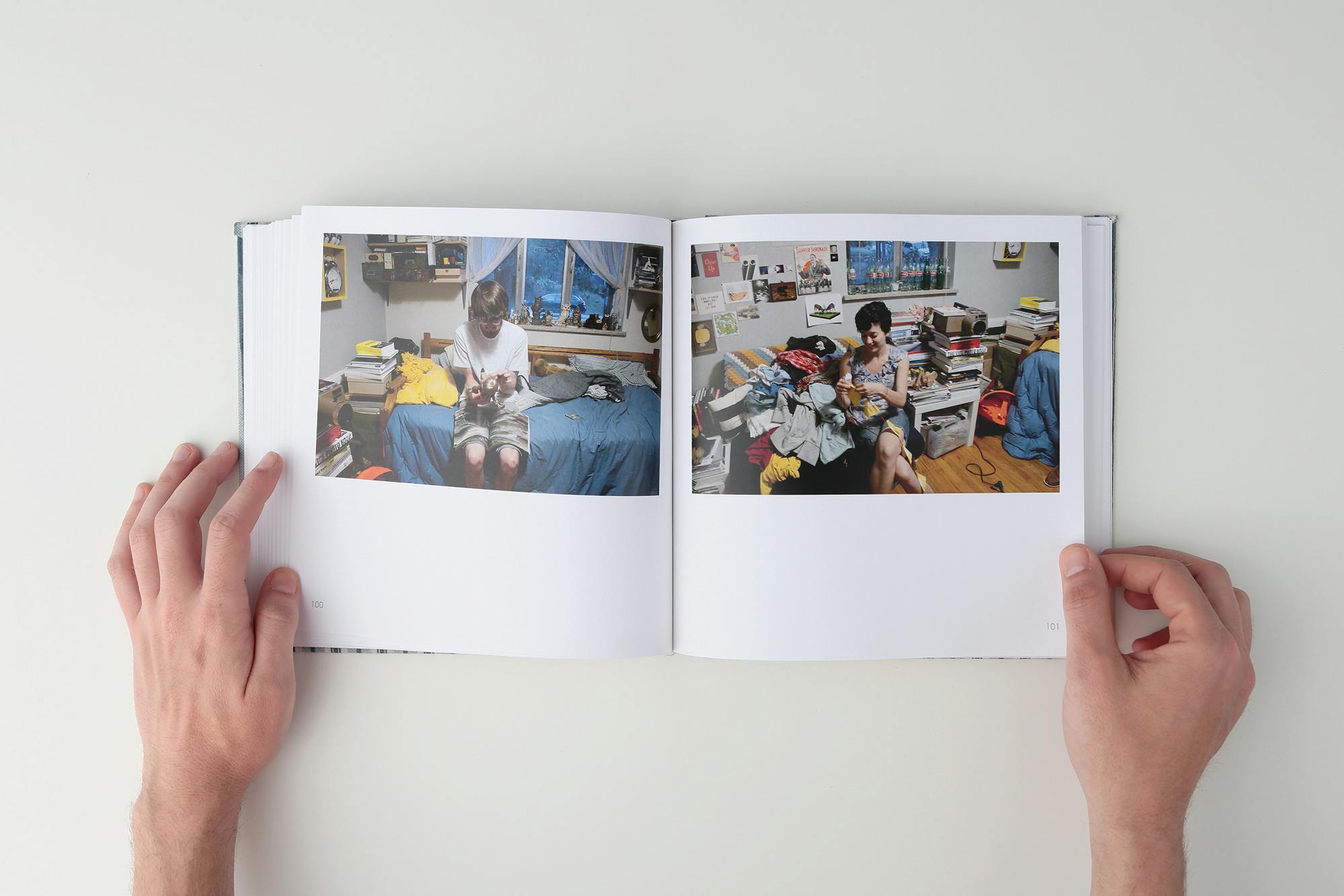

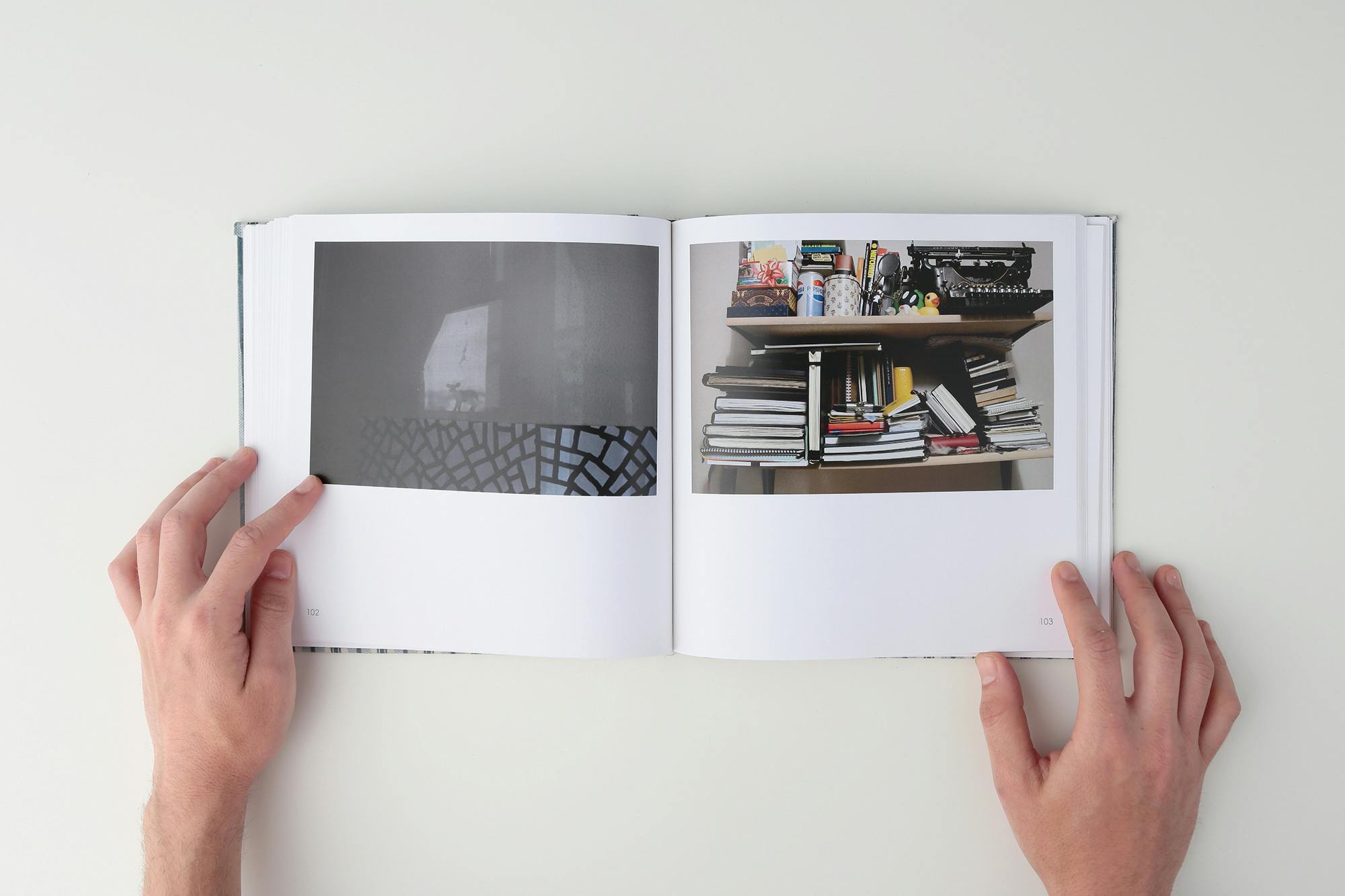

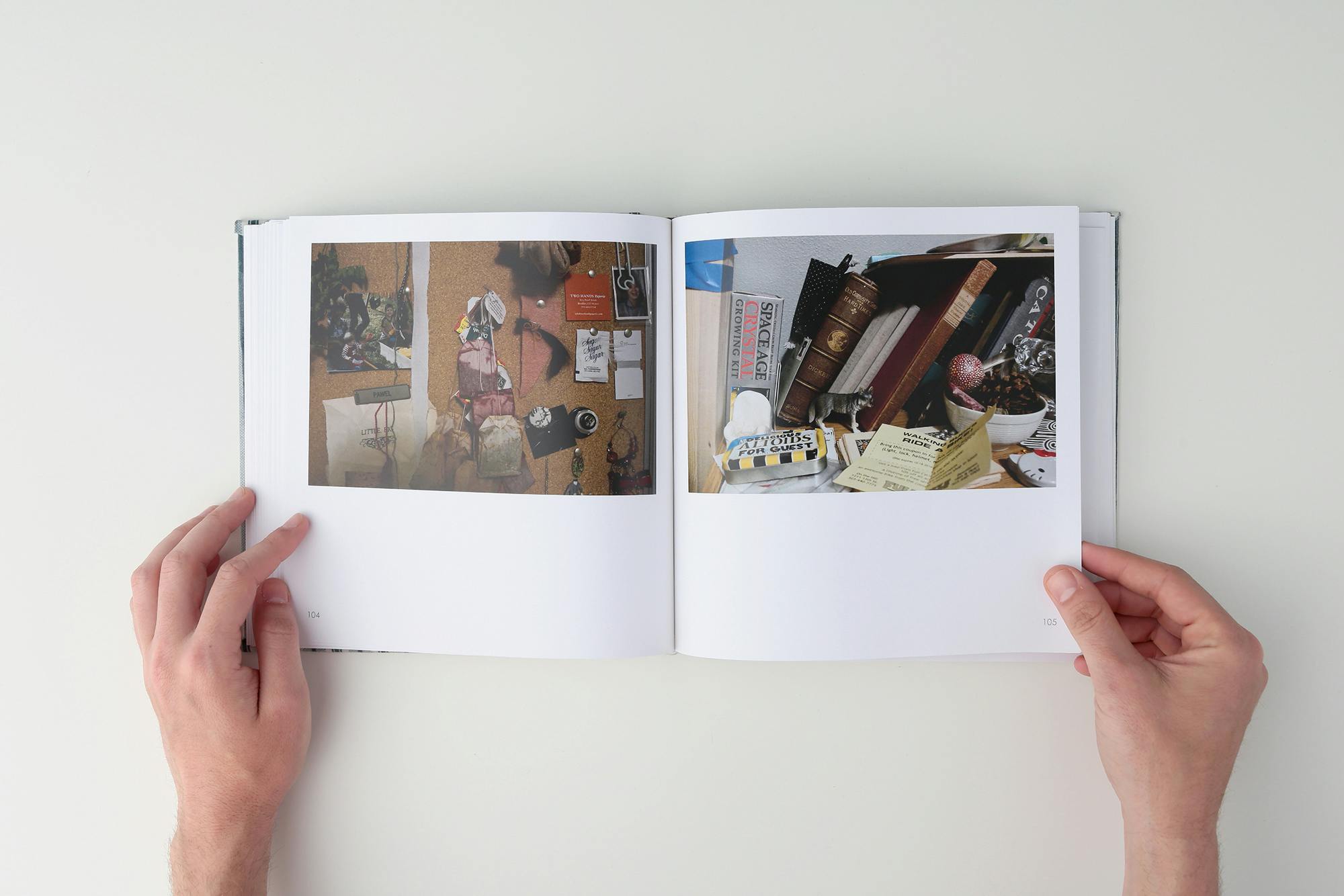

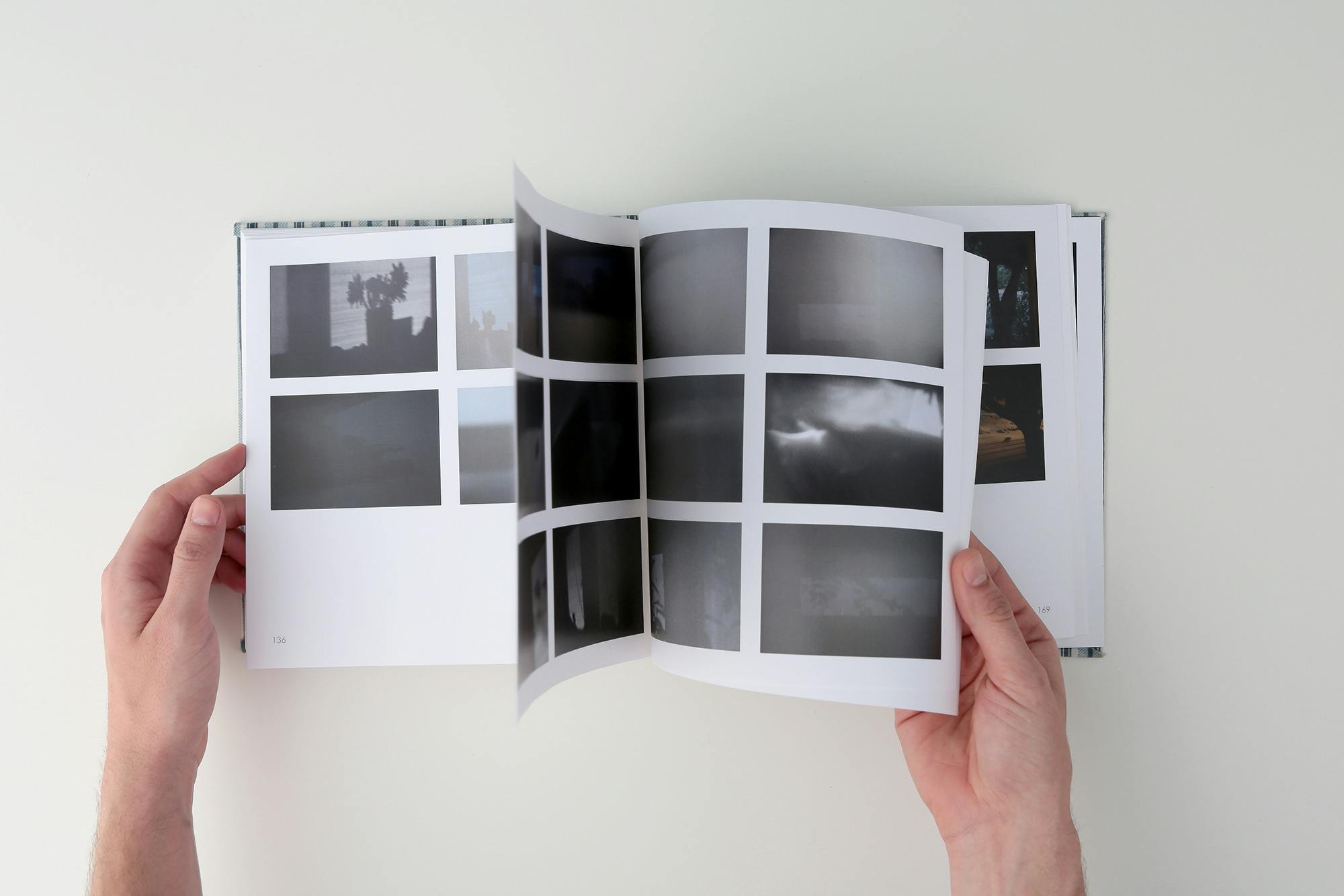

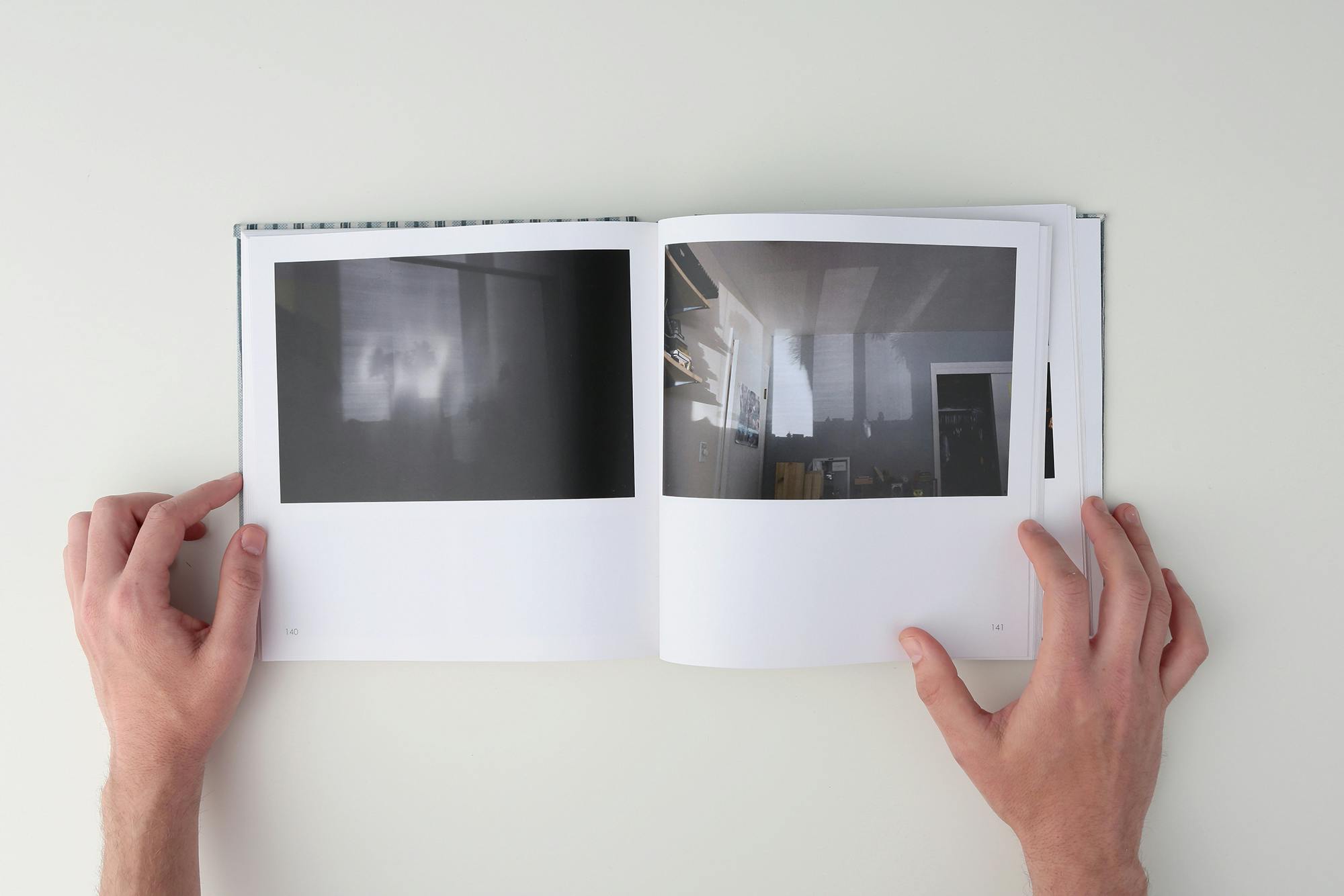

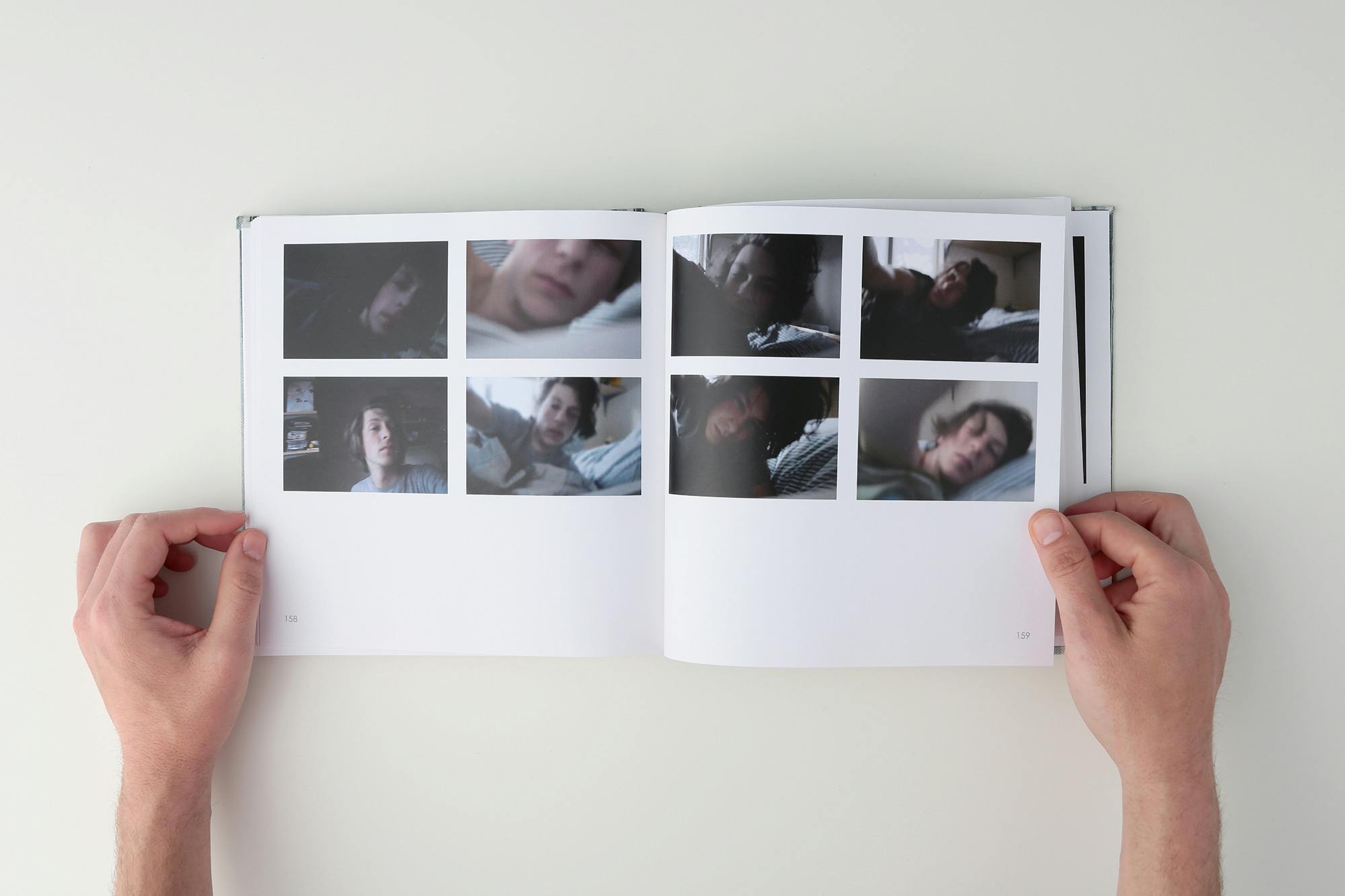

room Catalogue, 2010

exhibition catalogue, hardbound with bed sheet, with essays by Nicole Meyer

room Pamphlet, 2010

staple-bound, color, 10 pages; edition of 50

Essay by Nicole Meyer

Loving Objects:

Reciprocity and Collecting in Adam Milner’s room

Nicole Meyer

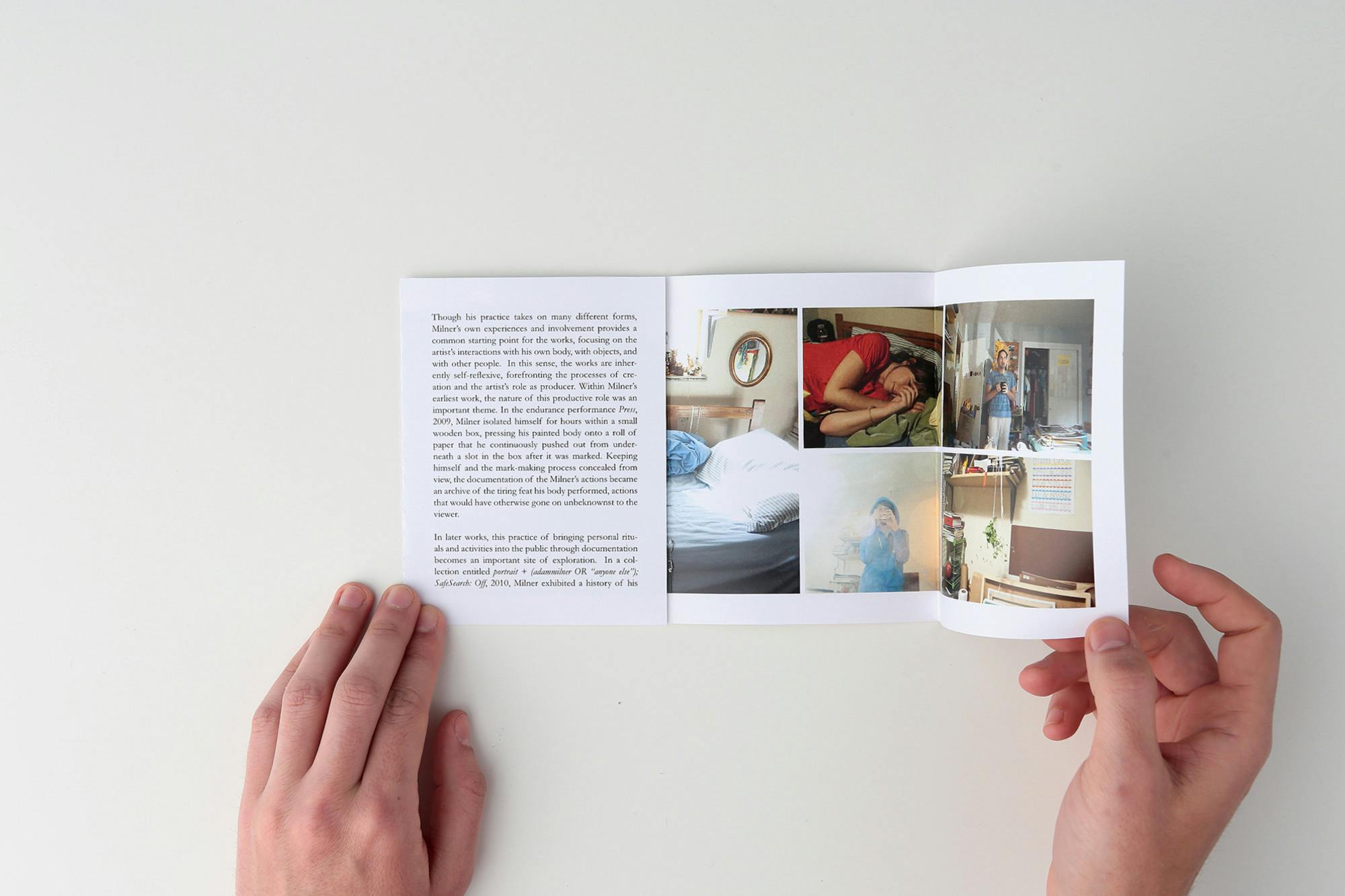

I’ve been in Adam’s room before. I probably come up in pictures, an object amongst objects, nestled and framed by the (White? Yellow? Biscuit colored?) walls. Visiting Adam’s bedroom is really more like being lovingly installed; tucked into a corner, onto cushioned bench, or under a quilt, you’re put in place. It’s easy to sink into the tableau; all of a sudden other objects are installed onto you, now you’re a supporting feature, a focal point. You work with that painting and this tin picks up the color in your socks. So does that tin, and that one. And the next... All of a sudden, themes start to stand out. Grouped or spanned around the space, objects begin to pop into sets, suddenly bolded with repetition. You get a sense that there are collections happening around you, that you are being taken up into a collection, even to the point that talking in the room necessarily becomes talking about the room. Objects tumble into conversation, getting mixed in with the words, lugging their stories behind them. Being in a bedroom, though, they necessarily engage with a narrative of privacy, memory, and everyday banality, all inextricably tied up with their owner’s identity. In visiting Adam’s bedroom, or really any bedroom, the idiosyncrasies in routine relationships between a person, objects, and ritual become unnervingly vulnerable. When this space is presented as a “ready-made installation” in Room, 2008-2010, the interplay between the artist and the objects presents a level of intimacy that both solicits and alienates viewer interaction—the viewer is incited to respond, though the stakes are higher than normal. In Room, it becomes clear that you are not dealing just with objects that can be lauded or rejected at will, but with the invitation to create a relationship with the artist both through those objects and as a kind of object yourself. The act of “collecting” then becomes a subtle and complicated encounter that co-constructs the identity of the artist as collector and the object (viewer or otherwise) as collected.

What I am attempting to tease out here is the uncanny nature of the collection; through the way it plays out Milner’s Room. What is a collection, and what kind of effects does this designation have on the participants and objects involved? What type of actions and qualities constitute a collection? Some insights into these questions are provided in cultural philosopher Walter Benjamin’s assembled thoughts on the “collector” in his unfinished Arcades Project. An enigmatic collection of fragmented thoughts and quotes in itself, the chapter on the Collector addresses the unique identity that collected objects acquire, distinguished from the regular, capitalist life of objects through the way that their value is not determined by use or functionality, but by an attribute shared across a group. Through becoming part of a “set,” these objects are given an individuality that makes them unique. Benjamin states, "What is decisive in collecting is that the object is detached from all its original functions in order to enter into the closest conceivable relation to things of the same kind. This relation is the diametric opposite of any utility, and falls into the peculiar category of completeness."

Continuing his meditation on the subject, Benjamin expands on what the experiene of collecting does for the collector. He notes, “Collecting is a form of practical memory, and of all the profane manifestations of “nearness” it is the most binding.” Proximity, memory, presence, and connection— according to the Milner himself, these form the basis of his artistic practice. But to describe them as “profane” is to call up a discussion of censorship, individual action, and provocation with solid precedents in contemporary art. This attention to the pressures on and condemnation of individual action arises in the works of performance artists such as Marina Abramovic and Vito Acconci, who have regularly solicited the participation of viewers in the gallery through provocative behavior, whether antagonizing or welcoming. In Milner’s work, everything is participating, objects and viewers. Any act or presence becomes participation, and past participants leave traces. As Acconci, in Seedbed, 1971, goaded response through a hidden but immediate sexual act, Milner’s bed (possibly unmade) and the documentation of other people within it conjure memories of bodies and sex with similar provocative presence. Like Seedbed, the clash of the private actions of the body and the public performance of viewing staged in museum exhibits meet tensely in room.

I don’t mean to suggest that it’s the antagonism and alienation of the viewer that the artist takes from the piece; that literally “gets him off.” To say that would be to ignore the intensely private practice that collecting and archiving can become. As “practical memory,” the collection is a kind of archive of individual action and assertion. In this way, Room is elevated from the abstract history of a bedroom into a work probing the struggle of processing individual experience within the pre-structured systems of meaning-making that govern involvement and communication. To create a collection is to tear objects from their narratives, to forcibly construct alternative possibilities and encounters, to recognize and acknowledge the unique character of each moment of wakening, or quick conversation, or statuette. By not using an object one is freeing it from its use value, its exchange value, and its identity as a commodity. New meanings and value are invented through its identity as a member of a collection. In this context, Benjamin describes the collector as an “allegorist,” deepening the understanding and possibilities of objects through writing new connections. Given these sort of progressive and self-asserting acts, the uneasiness of collecting relationships and encounters as if they were objects can be assuaged. After all, is it not the reduction to an exchange value and simplified, restrictive stereotypes that make objectification of experience so detrimental? In Room, too, many of the collected encounters, such as in series for Come Spend the Night with Me, produce objects from a collaboration of meaning making. The form these objects take, like the relationships created between the artist and the participant, are indebted to the unique way in which the two people work with and against each other. Even the room itself takes on different identities according the to the nature of the encounter—a stage as well as a storage place, a diorama and an enclosure, an installation and an environment.

In an article on Museology and Collecting, historian Donald Preziosi comments on the tendency (in histories of the museum) to conflate the practices of museums and collectors. This functions, he argues, to trace the lineage of museums to a harmless, idiosyncratic hobby of the renaissance aristocracy as a way to mask the political motives for the development of museums. If museums could be seen as a way of asserting and educating the public to a certain ideology, why can’t collecting have a similar power, if on an individual scale? When Milner invites the audience to both observe and participate in the creation of collections in room, he initiates a dialogue which places the power to create and assign meaning into the hands of the individual. This experience differs from the museum in important ways—it exposes the ability of collecting to change the significance of an object, forefronting the subjective force that shapes narrative and meaning within a collection. Further, it facilitates the creation of collective meaning through collaboration between the visitor/viewer and artist. As a result, room becomes an exercise in the creation of relationships both through and with objects, and leaving the space, the viewer has a heightened awareness of their own powers to assert meaning through the objects, encounters, and relationships that constitute experience.